In 1987, Barbara Cartland and Jackie Collins sat on Terry Wogan’s couch. Both deeply abnormal people (in a good way), both in deep disagreement. “It’s evil really,” says conservative Cartland. “What?” asks Jackie in a gold pleather jacket. “The books that you write, quite frankly.”

Now the similarities between these two powerhouses of fiction are manifold, but the difference between them is that one of them (Cartland) isn’t aware that she’s not normal, while Jackie is proud of the fact that she is. Cartland campaigns against a permissive society, sat there like a drag queen in a frou-frou pink dress, white face paint and diamonds, while Jackie’s books are testament to what happens when people are given permission.

When I was writing my book Diary of a Drag Queen, I thought about these two authors a lot. The book is wildly different in style to both of their writings—it would be foolish for anyone to try to emulate either—but I found it fascinating that both of them played with the concept of normality so much. To me, normality is a terrifying prospect. For some reason, the idea of normality has always felt synonymous with mediocrity, boredom, dissatisfaction. And neither of these writers traded in any of these things at all. I tried to write a book for people who have always found the prospect of normality scary, whatever their reason. For me, it started with not having an option to be so—I’m gay, non-binary, fat and a drag queen from a small town in the North of England—but when I’d finished my book I realized that being not normal had been the greatest gift I could have possibly received from society.

The following are books that view the world from different positions, but all from places of not being “the norm.”

Against Memoir: Complaints, Confessions & Criticisms by Michelle Tea

All I ever want is to be inside the mind of Michelle Tea. When my friends and I first discovered her books some years ago we passed them around like wildfire, creating WhatsApp groups to claim characters in Michelle’s real life as our own. Tea has lived the queerest life. No, Tea has lived five of the queerest lives, and she writes about it with such a knowledge of who is going to be reading her words. These books are so precious to so many queers because she’s written them for us. There’s no explainers, it’s just her writing about us, parts of us, for us.

Against Memoir is a collection of essays on topics that interest the author. It’s my favorite of her books—Black Wave a close second—because you can pick it up and imbibe a slice of Tea’s mind in five minutes. More than that, it helped all of our friends become a little bit more like our idol: now we love Gene loves Jezebel and Erin Markey follows me back on Instagram. She reminds so many of us lost queers of the joy of it all, of why we were all drawn to this life lived elsewhere.

Secret Diary of a Call Girl by Belle De Jour

This was the first book I ever read cover to cover. I was 18 and on holiday in Benidorm (if Miami and Vegas had a cheaper, slimier baby) and I borrowed it off a girlfriend who had always been obsessed with sexy chick-lit. It’s arguably an easy read, a sort of erotic Bridget Jones, with a devolved sense of its own politic. But in a pre-woke world this iconic piece of pop culture, or low culture as many literary snobs would like to name it, was where my obsession with life writing started. The book details the life of Belle De Jour—a book-smart sex worker who is incredibly expensive to hire, and who, like the rest of us, is trying to work out how to balance a widely castigated means of income with her personal life.

We didn’t read much growing up, because in Northern working-class culture gossip and soap operas are what make up the bulk of our entertainment. I’d found books we were forced to read at school—Dickens, Shakespeare — dull, not for or about me at all. But when I opened Belle’s book, it was the first time I’d felt understood by a character. Perhaps because she was living on the outside of sanctioned society, as was I, or perhaps because the prose is personable, playful and oftentimes powerful. Whenever I come to write personal essay, I think of Belle, of how scandalous simply writing your experience can be, and if that doesn’t help get through the block I’ll often put on a sky-scraping pair of heels and channel my inner De Jour.

Poor Little Bitch Girl by Jackie Collins

As expected, I’ve always been obsessed with Jackie—from her life story to the fact that so many people thought of her as vulgar and yet she’s one of the best-selling authors of all time. I think it’s remarkable, and truly very camp, that to achieve such sales figures many of her detractors must have been secretly stashing their Jackie tomes under their pillows, out of sight of judgemental friends who were probably doing the exact same.

Jackie’s writing is the definition of glamour, even when the scene is scary or tragic. She paints pictures with the worlds we know, by looking at them always from the viewpoint of the insider. Because, even though the books aren’t about her per se, you know that everything in them is something she has seen. Roman a clef. Which makes reading them all the more glorious—like a game of Guess Who!

Poor Little Bitch Girl is on this list because it’s the one I most recently read, about high school friends reunited through a mysterious, high profile death. But really, I could put any Jackie on this list and be happy with the choice. She is unmatched and her very existence proves the deep immaturity of our society: that people are still shocked by her work, as a woman writing about men and sex, belies how conservative our world really is. Jackie taught me to lean into the shock. Jackie taught me how to be a drag queen.

The Vegetarian by Han Kang

I’m not a vegetarian, but this book is about more than meat. It’s about finding a metaphor by which to reject and renegotiate patriarchal control. In this instance, it’s giving up meat and, eventually by the end of part three, becoming a tree. It’s a book which goes deep, yet remains subtle, into the depths of despair that can be brought about by being controlled or oppressed. It’s about domesticity, and about how rejection institutions—both big and small—create friction that eventually spreads through this family structure like wildfire. This book rejects normalcy, but it doesn’t scream about its doing so.

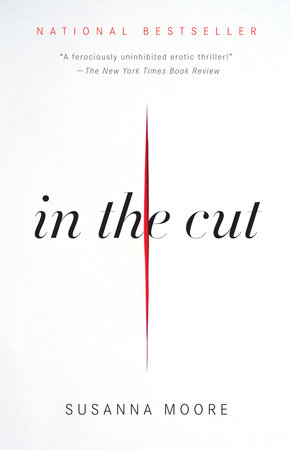

In The Cut by Susanna Moore

I haven’t seen the film, but I’ve read this book twice (the only book I’ve ever read twice). Moore’s lead is complicated and judgemental—a woman obsessed with language, a teacher whose fantasies are laid bare. This book is so powerful because its gender politics are uncomfortable. It’s about male violence and desire for men. It’s an erotic book, and yet it confronts violence towards women, at the hands of men, within the same scenario, unpicking the fact that these two things might well be linked. That’s hard to do: when male writers do it, it’s often with stories of murder and assault. And while In The Cut is set around a murder, that Frannie (Moore’s lead) and the detective she’s sleeping with are both linked to in different ways, it’s not insensitive to the violence, but it doesn’t obsess over it either. It illustrates the way so many women navigate the world when male violence is a constant threat, and while it was published in the ‘90s, it’s as brand new a book as anything released today.

Role Models by John Waters

Waters’ writing is so beautifully non-judgemental, it makes an art out of seeing everything with value—venerating low and high culture with equal importance. This practice has informed so much of how I both write and see, treating people’s emotions and tastes as something valid to their experience. What Waters also does so dextrously is expect the highest of people, never applauding people for being good people—simply expecting it of them. Icons is a rare insight into what creates an abnormal auteur. Some of the book is uncomfortable, and Waters’ viewership can often feel exploitative, but when it clicks, it clicks so powerfully that Waters, as in his movies, subverts acts deemed socially so shameful into things so powerful, so iconic. An interview with his friend Leslie Van Houten, a Manson devotee who remains in prison, caused a stir. But what Waters communicates to those of us who live on the edges of society is that everyone deserves a chance to be heard. And that is a powerful thing to understand when you belong to a community that so often isn’t. I love this book.

Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex by Judith Butler

I’m unsure whether Butler meant for every word in this book to be understood, but most of them can be felt. Inside these pages was where so many of us who find ourselves diverging from the normative gender binary understood, for the first time, not only that what we are is real, but why we are real. Or more accurately why binary gender is not real. Until reading Butler, I’d only ever understood a construct to be something that was made in a physical sense, not in a metaphorical or social sense. I can’t describe what a 22-year-old wearing a dress in a stuffy university library felt when they found such a mirror to themselves. And really Butler sits at the top of the pile of which I am at the bottom. So much of my book Diary of a Drag Queen aims to explain what Butler taught me in language my mother can understand, that I can understand.

The post A Drag Queen Recommends 7 Books About Rejecting Normality appeared first on Electric Literature.

Source : A Drag Queen Recommends 7 Books About Rejecting Normality