Christopher Manson’s “Maze” cast a spell I’m still trying to shake off decades later

“This is not really a book. This is a building in the shape of a book… a maze.” —From the directions to Maze, by Christopher Manson

I first read Maze as a child, on a bus. I don’t remember where the bus was going (I’m not even sure it was a bus — maybe it was a van?) because I was thoroughly and instantly inside the book. From the first page, I felt stifled and scared, full of an obsessive drive that I otherwise only associate with moments of sexual awakening. The words of the directions functioned like a spell. The book told me that it was a building, and then it was. And I was trapped inside.

Maze, published in 1985, was part of a mini trend of picture puzzle books with real cash prizes, patterned after 1979’s Masquerade. But where Masquerade was dreamy, off kilter, alarming — it seemed to open up somehow to the possibilities of a world of mystery — Maze made me feel like I was sneaking off to read porn. It was like disappearing into a hole.

The rules are simple. Each page, numbered 1 through 45, is a room in the Maze. Each room has numbered doors that lead to other rooms. To go through a door, you turn to the indicated page, where you will be faced with another room full of doors and mysterious objects, depicted in Manson’s architectural black and white engravings. Your aim is to reach the center (room 45), and then escape back out to room one, in no more than sixteen steps.

When I started work on this article, I was reluctant to pick up the book again, even though I’d remembered it with intense emotion for decades. But Maze was memorable because it was unpleasant, like a drug that shows you the places where your brain can break. I’d spent what felt like days at a time dissecting its images and mapping its paths, getting stuck in its loops and traps, wanting to quit but unable to put the book down until I opened one more door, tried one more path. Rooms leading into rooms, a secret that you are trying to uncover, a chase. A sense of fascination that makes it difficult to lift your eyes or leave your house.

The truth is, I feel the way Maze made me feel all the time now. The big difference between reading it and wandering through the endless rooms of the internet is that with Maze, we are assured that there is a solution. There is an escape. There is even — if we are especially clever and worthy — a meaning.

With “Maze,” we are assured that there is a solution. There is an escape. There is even — if we are especially clever and worthy — a meaning.

Because the maze doesn’t just have a solution—it also has an answer. There is a riddle hidden in room 45, with the answer concealed somewhere along the shortest path. And this answer was valuable, not just because of how well it was guarded, but in the grossest commercial terms. Like the riddle of the Sphinx, it had multiple rewards. A publicity campaign offered a ten thousand dollar prize to the first person who could provide all three parts of the solution, but by the time I got my hands on the book, the campaign had concluded.

=> No monetary award enticed me into the Maze. It generated its own sickening fascination.

=> Decades later, the book maintains a dwindling but enduring cult.

=> The campaign had concluded — but no one had won.

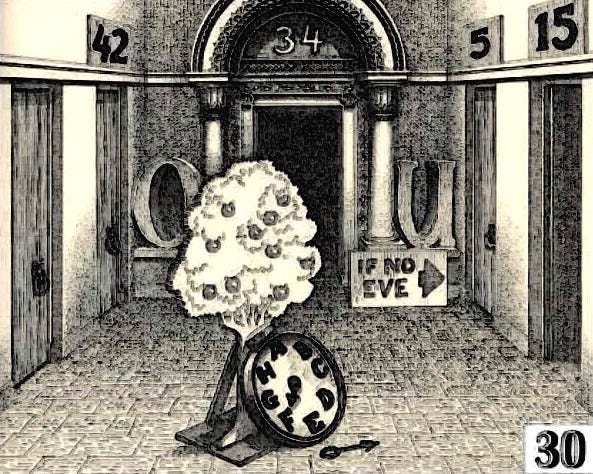

ROOM 11

A fair amount has been written on the toxic appeal of clicker games. I try to stay away from them. As a child, I had to ban myself from Tetris because I had stopped doing my homework, and started having geometric, multi-colored dreams. I have never been diagnosed with any kind of obsessive compulsive condition, and I have no reason to believe that I have one. Games do this to me because they are designed to do this to me. The whole point of Tetris is to get you to dream about Tetris, to rewire your brain the way a fetus rewires a pregnant woman’s blood vessels, just so it can live.

Maze was the first work of art that I’d seen turn this nasty impulse into storytelling. There are others — especially now, in this era when the Maze extends everywhere. The ones that stick in my head are digital but low tech, achieving their effects with text and the most minimal of graphics. They also (mercifully) have specific end points.

Games do this to me because they are designed to do this to me. The whole point of Tetris is to get you to dream about Tetris.

The astonishing Universal Paperclips uses the perversity of clicking, cannily, to force its player to inhabit the role of a monomaniacal AI, first compulsively generating paperclip after paperclip, but eventually — as the paperclips start to pile up — going on to dismantle the world and conquer the universe. Universal Paperclips has no secret solution, just an objective that you can (must) achieve. But like Maze, it uses the human capacity for obsessive repetition as the engine for its story.

Porpentine’s classic Twine game Howling Dogs takes this feeling of being trapped in a game as a subject. It is also (spoiler) an escape maze; using hyperlinks instead of pages, it spins you in repetitive, exhausting loops full of illusory choices and overwhelming information. And, just as in Maze, there is one simple trick that will let you break the loop and access the center.

What makes this kind of puzzle so devilish is that obsession blunts your ability to shift your perception.

=> Moving between the gears — between the dogged grind and the moment of inspiration — is the key to solving any problem.

=> It is possible to win, but also possible to lose.

=> Maze is so thick with contradictory symbols that you have to put on blinkers to move forward. If you tried to really look at the thing, you’d turn to stone.

ROOM 27

For the history of the puzzle, and its solutions, I turned to Into the Abyss, a website created around 2013. With its comment sections, minute focus, and esoteric design, it feels like a part of the net that is lost, that we are already mourning. Presented in an impish cosplay version of Maze’s goth masonic style, it was maintained by its founder, who went by the pseudonym White Raven, for precisely 45 months after its inception. (Forty-five months, 45 rooms. White Raven vanished, presumably, for numerological rather than sinister reasons.)

But the Abyss is not abandoned. There is a dwindling online Maze community, composed of people who, as one commenter put it, “remember how much this book creeped them out when they were ten.” There are recent comments — including several from today. Many are from the same poster, whose handle appears to be his full, real name. He has an impressive history of essay-length comments on the possible symbols and connections between each room. Clicking through the pages and seeing his name again and again, it is impossible to avoid imagining him as one of the maze’s victims, permanently trapped in a loop.

Browsing Into the Abyss makes you acutely aware of the passage of time, of just how much has happened while you’ve been opening doors and hunting down clues.

=> For example, White Raven, in a brief essay on the immersion puzzles inspired by Maze, muses about the possibility of “Immersion Puzzle Real Locations.”

=> Is there a chance that, even in the age of infinite information, the Maze is still dangerous?

ROOM 14

I put off writing this article because I wanted to make a good faith effort at solving the central riddle of Maze. This was arrogant on my part. With ten thousand dollars on the line, it wouldn’t be easy. As it turns out, it was even harder than that. Because no one had defeated the Guide in time, the publishers had to extend the deadline and release a set of hints — twice. Finally, they released the exact solution and gave the prize, split into even thousands, to the ten people who got closest. It has the rare glamour of a puzzle that has, technically, never been solved.

=> Is it possible to make a puzzle that is both too hard to crack and not total bullshit?

=> Of course, in 2019, it’s a lot easier.

ROOM 5

One of my philosophies about storytelling is based on the idea of a labyrinth. The harder it is to get through your labyrinth, the more your reader will like it, and the more they will value what they find at its center. It’s a trick used both in twisty genre fiction and impossible and esoteric books like Ulysses — make ’em sweat, make ’em feel smart, and they’ll remember what you have to say.

Designing a narrative is exactly like designing a puzzle — a riddle, say, or an escape room. Balance is important. You want to challenge your guests to the very limit of their ability. You want them to get it in the nick of time. And yet, you have to be fair.

=> Even if you are trying to appear aesthetically treacherous, you still must be fair.

=> For a while, this was part of my day job.

ROOM 24

I still remember the actual chill I felt the first time the Guide deposited me in the inescapable darkness of page 24, the room with no doors. “You are here with the rest of us now…” says a voice in the dark, as the Guide, laughing, abandons you.

Room 24 was terrifying. And yet, it was also a release. There were no more doors to open, no more secrets to chase. There was no more reason to try. Perhaps the sensible thing to do, when you reach Room 24, is to admit defeat and lie down in the darkness.

Sometimes, I think it was a mistake to go back to the beginning, a mistake to try again. Because (as you know if you, like the rest of us, have trouble even leaving your house on certain days) when you actually try to escape the maze, the sense of being trapped only gets more overwhelming. This house is not only made of stone and mortar, wood and paint; it is made of time and mystery, hope and fear.

This was the difficulty in returning to the Maze. I live there all the time now. I don’t know if I ever got out.

ROOM 4

In 2018, I worked, briefly, in an escape room, one of those real-life immersion puzzles that have mushroomed up across America in the past few years. This idea must have seemed like a fond and childish dream to the founder of Maze fansite Into the Abyss, who wrote in 2013 that “This type of ‘puzzle in the shape of a location’ is a mainstay of fantasy literature and film but, as far as I know, one has never been constructed.” (They seemed more bullish on the possibility of game locations existing in virtual reality.) I was a keyholder, sole ruler of the little eight-room kingdom, which mean that I did everything from book appointments to wipe baseboards.

The Video Game That Shows Us What the E-Book Could Have Been

My favorite duty was giving hints. My escape room was a chintzy mall chain establishment; the rooms were basic, and the puzzles cheap, but there was a kind of delight in the way boredom and frustration gave way to sudden breakthroughs. I had to phrase my hints carefully so as not to rob the customers of that feeling. For whatever reason, I found it easiest to strike that balance using a sadistic, teasing tone. It was delightful to watch people struggle, and even more delightful to watch them figure things out — a perversity that I connect with in the mysterious guide.

=> This is a recent development. As a child, I found the guide not sympathetic, but sexy.

=> I have some personal experience with this, beyond that day job. I’m a playwright and I care very deeply about constructing mazes for my guests.

ROOM 33

Manson’s guide is at minimum aesthetically treacherous — an unreliable narrator who keeps winking at you about his plans. There is, throughout your journey through the book, a definite sense that he is trying to fuck you. He is definitely trying to fuck the rest of the group. You can see inside his head, and he’s always getting anxious that they might notice something, or privately crowing at their stupidity. He is sinister from page one, when he says “They think I will lead him to the center of the maze. Perhaps I will…”

There are no drawings of the guide, but in those ellipses you can almost see him steepling his fingers like Jafar.

=> You want to trust him, but you can’t.

=> You don’t want to trust him, but you have to.

ROOM 26

Manson had wanted to call his book Labyrinth, but the publishers were anxious about the (then upcoming) David Bowie film, which is, like The Phantom of the Opera, another story in which a sadistic and mysterious man holds sway over a treacherous but expansive piece of real estate. This has always been a good way to get my attention.

There is a particular person in the group of nebulous characters traversing the Maze — gendered as female and described as smarter than the rest — whom I quite clearly identified with, whose story I longed to see elaborated on. At one point, she looks the guide in the eye and asks if he has picked flowers for her. “I had to tell her the truth,” he says, but we never get to know what the truth is.

These unexplored stories, this sense of personality, is part of what makes the book feel bigger than its pages.

=> That, and Manson’s unmistakable style.

=> That, and the way the book invades your mind.

ROOM 30

Manson’s drawing and writing are of a piece: creepy, mannered, austere, but also gothically compelling. The book has the same kind of removed Masonic stiffness that makes the Rider-Waite tarot decks so fascinating. You have no idea what’s going on, but it’s a lot, and it all seems packed with hidden meanings. As the directions tell you: “Anything in this book might be a clue. Not all clues are necessarily trustworthy.”

Within the 45 rooms, the variety is endless. You step into high wind-swept places and fall down slides into dark caves. You rest in comfortable drawing rooms, take in puppet shows, hear music, dig beneath forbidding statues, and sometimes find yourself shrunk to the size of a mouse. The weather is always changing, and everywhere you go, you are meant to be looking for clues.

In just one (relatively sparse) room, there are: two giant carved letters, a fake apple tree, a giant watch with letters for numbers with the hour hand pointing at F and the second hand pointing at door 15 (which is open) and a sign saying “IF NO EVE” with an arrow pointing at door five. All of the doors are identical except number 34, which is unusually elaborate, and only one of them is the right choice.

Elsewhere, the bottom half of a painting appears to depict the feet of two monsters, one standing still, the other creeping up behind the first. Other pictures depict a wide assortment of human faces, in an assortment of styles, with an assortment of unsettling expressions. Umbrellas appear everywhere, along with variations on the same white bird (full grown, baby, toy). Also there are hats — a whole vocabulary of hats making long incomprehensible sentences, along with lots of signs and symbols that just plain don’t make any sense. These oddities are sometimes referred to darkly in the text, sometimes ignored, and sometimes cackled at by the guide, who is constantly alluding to his parents, his violent past, and the irrevocable doom of his guests.

In fact, it is impossible for everything in the maze to have meaning. It is a crush of meaning. It’s overwhelming.

The fastest way to get to the center is brute force. Ignore the guide, ignore every clue, try every door, make a catalogue and write a map.

Once you do that, you’ll see that getting to the center is impossible.

=> You’ve missed a trick.

=> You need to look at it another way.

ROOM 29

And that, in the end, is the key to getting to the center of the Maze, if not the key to solving the riddle. You take one simple, physical, real-world action and then… like magic… it appears. A hidden door that takes you to the center.

There’s something in Maze that I’ve learned to resent a little — the idea that there is a key. That a single trick will let you into the heart of the maze. This idea bothers me. I’m opposed to it, philosophically.

But perhaps I’m being unfair. The trick is only the first step. It doesn’t let you escape. It doesn’t answer anything.

=> It only leads you to the riddle of the maze.

ROOM 45

The answer to the riddle, hidden along the path is, in fact, another riddle. And the answer to THAT riddle, hidden in plain sight the whole time, is “the world.” The world’s most challenging puzzle. Get it? It’s a house we all live in, a place we can never escape.

A poster on fan site Into the Abyss notes that the Maze has no exit. After you get to the center, you take the shortest path back to room one, where there is a visible, sunlit archway that should lead back outside. It seems to be the other side of the archway from the prologue, which is marked “THE NEXT PAGE,” but it has no number. It has no title or instruction. According to the rules of the Maze, there is no way to pass through it, no way back out after you enter, even if you avoid the trap, and attain the center, and answer the riddle and identify the guide…. you are still trapped here, in the world. The monstrous walls rise up and run away as far as the human eye can see, circling and dividing. Which half is the Maze? Under these circumstances it is good to remember that this is not a building, it is a book. Close it.

A Labyrinth in the Shape of a Book was originally published in Electric Literature on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Source : A Labyrinth in the Shape of a Book