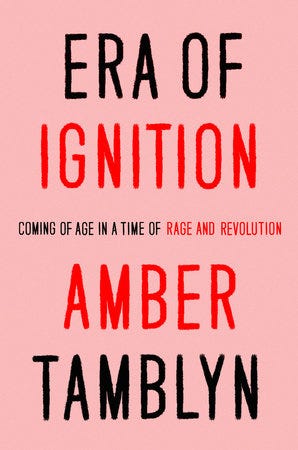

The author of “Era of Ignition” talks about white feminism and its shortcomings

Amber Tamblyn was going through a rough patch. The night before her wedding to comedian David Cross, her agency called and dropped her as a client. She responded by throwing her most expensive shoes into the East River and pissing on a statue in a Brooklyn park. Two months later, sitting next to Cross at a bar, “I gulped down my bourbon and proceeded to tell my husband that I was pregnant but was planning to terminate the pregnancy,” she writes on the first page of her book, Era of Ignition.

The book continues thus: painful, surprising, funny, honest, incendiary. As Tamblyn’s personal life was flatlining, the country, too, was in a time of crisis and rebirth — the 2016 election, the #MeToo movement, and the recognition of centuries of inequality. Era of Ignition: Coming Of Age in a Time of Rage and Revolution is a personal examination of what she considers a fourth wave of feminism in the US. The actress/director/activist explores workplace discrimination, the expectations of motherhood, sexual assault, male allies (and their shortcomings), white feminism (and its shortcomings), and how to show up in solidarity for women of color.

Tamblyn and I talked about reckoning with men in our lives, consuming problematic media, how social media can eliminate essential dialogues, and more.

Katy Hershberger: I so enjoyed the book and once I started I couldn’t stop reading. I loved how, in a lot of ways, it’s so funny and it sort of stands against this idea that feminism is humorless. Do you get that a lot, people being surprised that you’re funny?

Amber Tamblyn: No. I mean, maybe they do to a certain degree, especially because I think I’ve sort of not had such a sense of humor since Trump has been elected. I feel like many people feel that way.

KH: I feel that way.

AT: Yeah, I feel like all of my ability to laugh things off has gone out the window a little bit. But I do sense that that’s returning and I think in the writing process of this book, of returning to some of the old stories, especially pertaining to my experience in the entertainment business, they’re so morbid or dark that you can’t help but laugh at them, so the retelling of the story is framed sometimes in a humorous way.

I don’t think it’s that we should be erasing the art of problematic people but I do think it’s really important to be conscious of it and be conscious of what we’re consuming.

KH: As someone in the entertainment industry, how do you think we should look at art that is problematic? I mean, pretty much everything in the last fifty to 100 years is at least a little bit problematic. It’s sort of easy to reject Woody Allen movies but for example, I’ve been re-watching Cheers and the Sam and Diane relationship doesn’t seem quite as sweet now. How do you, as someone within the industry and also a viewer, reconcile some of those things?

AT: For me it’s very complex but I think the power is in the awakening, is in the knowledge of the artist behind the work. And the very fact that you would see that show in a different light suddenly, I think is in and of itself very powerful. I don’t think it’s that we should be erasing the art of problematic people but I do think it’s really important to be conscious of it and be conscious of what we’re consuming, and sometimes consuming to a degree that is taking away from the stories and the narratives of other people who would never get a chance to be seen with a large machine behind them, like someone like a Woody Allen for instance. So again, I think everything is just in the acknowledgement of it and just being aware.

Honestly, I feel this large cultural pivot in a really important way towards not talking so much about problematic work or problematic people. I think we’ve had that for the last two years pretty prominently and to me, when people ask about that, this happened at an Emily’s List panel in Los Angeles that I did recently, a reporter asked that and I just felt like, I don’t want to talk about them or their problematic work. I want to talk about the show Pose or the work that Ava Duvernay is doing. I want to talk about the important artists of our time who are changing and re-sculpting the way stories are told, but also the way stories are valued. To me that is what’s most important. So sure, let the film Manhattan continue to be the classic that it always has been, but I’m not gonna sit around wasting time talking about it or talking about the man behind it. I know how I feel about him, most everyone I know knows how they feel about him, and there’s too many great — powerful and not powerful too — women who are trying to have that power. There are too many amazing artists that are on the rise right now and they deserve all of our attention.

Amber Tamblyn’s Book About a Female Rapist Is One of the Year’s Most Feminist Novels

KH: In the book you really thoughtfully discuss having these conversations with your husband directly too. And I think a lot of women now are trying to figure out how to talk about this with the men in our lives, especially if they’re well-meaning but perhaps misguided sometimes. How do you think we do that? How do we reckon with that, how do we teach them and forgive them for these mistakes they might have made?

AT: To me the work is in the conversation. I think that all real systemic change begins with a dialogue, not a monologue on either side, which means it’s not enough to just feel the way that you feel and believe what you believe and then say “why aren’t people just getting it.” And it’s also not enough for men to feel the way they feel and know “this is just what I believe and I don’t need to change.” Women too, it’s not just men that are a part of that larger problem, it’s a problem of power and it’s a problem of the way that power is dispersed. So to me the monologue happens when it’s just me standing over here going, “I’m a smart feminist, why can’t other people just figure it out, why can’t men just be better, why can’t certain women just be better.” Or when a man or somebody else is also doing that on the other side. Saying, “I’m over here and I know what I know and I believe what I believe, this is who I am and why can’t these people just figure it out and meet me halfway.” And instead I think it comes with really complicated, more difficult dialogues that should happen in person.

We’re a culture that fights a lot over the internet and has a lot of point of views on social media, and that’s fair and really valid and has certainly given a lot of people voices that didn’t have it before that deserve to be part of the cultural narrative, but at the same time I think when we’re having personal conversations with people that we love, with partners, with parents, with sometimes our own children, whether we are being taught or whether we’re doing the teaching, that has to happen at a dialogical level. It has to happen as an interaction where two people are being heard and two people’s thoughts and opinions and emotions can be valued at the same level and that’s almost impossible to do on social media, in any other place than in a real dialogue. I wrote those chapters because I’ve spent years now talking with women, especially women who voted for Hillary Clinton and felt like very fierce advocates of hers, who felt like they were not only not being heard about why her physical embodiment was so important, but also just not seen, they just didn’t value their opinions on the matter and so I wanted people to really think about when they get tired, when women get tired of having these conversations you’ve gotta remember that there are also other people who are tired of having those conversation with us as well. And so that means we have to keep having them. We just have to keep doing it. It’s hard, but that’s how change happens.

I get this sense like the greatest fear of white women is to be accused of not being feminist, not being allies, being racist, or doing a racist thing.

KH: You mention one way in particular that we need to have these conversations, and you write about owning the title of white feminist so that it won’t own you. I was hoping you could talk a little more about what you mean by that.

AT: Yeah, I think this a really tough, again something that’s deserved of a dialogue, people sitting together and having those conversations. But I get this sense like the greatest fear of white women is to be accused of not being feminist, not being allies, being racist, or doing a racist thing. I think the most important thing that any person can do whether you’re white woman or a white man, whatever you are, is to put down the defense before you make a decision. And because your emotions immediately take over and you immediately want to defend yourself, which I understand, that’s a natural human instinct, anybody wants to do that, but the truth is that in the examination is where you will find growth. Personal growth. So pausing before you have that defensiveness and thinking “ok somebody has made this accusation or somebody has told me that I’ve hurt them, it is now my responsibility to take that seriously and to examine it and to think about the way my actions are not defined by my own morals and my own beliefs but defined by the experience of the other people who are not like me.” That is the most important thing that you can do. So by owning that word and talking about it not having an onus back is just by saying “I own the worst parts of me and I’m not afraid to be called out on them and in fact I appreciate being called out on them, I appreciate being told when I’m harming someone.” That is not a joy that anyone likes doing, whether it’s black women, whether it’s us, women as a whole having to constantly talk about things that men are doing wrong. I think the larger culture thinks we find some joy in that, but it’s exhausting. It’s exhausting for anyone. So the important thing to do is start to take some of that responsibility on ourselves, each of us individually, no matter who we are no matter where we come from.

I own the worst parts of me and I’m not afraid to be called out on them and in fact I appreciate being called out on them, I appreciate being told when I’m harming someone.

KH: Tell me a little bit about the decision to include an essay from Airea D. Matthews and an interview with Meredith Talusan.

AT: First of all they’re both dear friends of mine and I did feel [that] to write an essay about censoring marginalized voices or non-white voices would be slightly hypocritical unless I actually walked that walk instead of just talked that talk. And so it occurred to me that a large body of my readership is white and feminist and it would be really nice for them to not only hear a piece written by someone whose work I really admire like Airea D. Matthews, but also the experience of somebody like Meredith and to really see how the most important thing, as bell hooks would say, is that feminism should be for everybody. That to me is the ultimate gold standard. If we can say, look, there’s nonbinary people, there’s cis white men, there’s feminists of all kinds, all of these different types of people believe in feminism and call themselves feminists. It’s not enough just for women to do it, it just isn’t. It should truly be for everybody. So for me adding their voices in the body of the work was both making sure that it did feel like a fully rounded-out thought, that essay, it didn’t just feel partially finished. Also I think a really great way, within the body of the book when you’re having such a difficult conversation within an essay which actually isn’t even an essay, it is a monologue, to follow it up with a dialogue between two people like me and Meredith to show a literal dialogue happening about things that are difficult.

KH: It’s so interesting to be able to do that in print.

AT: Yeah, it was fun. We went and had a couple glasses of wine and put a tape recorder out and just talked.

KH: That sounds like the perfect way to do it.

AT: Yeah. Meredith’s perspective… I’ve known her for a while now and I’d never even thought about it that way. The privilege of having both experiences, so you’re really able to say what is and isn’t sexism, what is and isn’t misogyny from a literal perspective. Not just a feeling, but saying “this is the fact because I’ve been on both sides of those genders and I know how that feels.” That blew my mind when she said that.

KH: When Meredith said “I’ve watched this happen presenting as a male and now my voice is so much less heard.”

AT: Yeah exactly. And to also be able to then see the problems within any attempt to lift up voices that are not, again, white and female or white and cis, and you really get a different perspective that way. That’s what it’s all about. What I love, what I love about the world, what I love about this country in particular is that, despite the graveyard this country is built on, we still can rise to the occasion and harness these difficult conversations amongst us and really appreciate and learn to value our differences, the differences that are equal in importance and equal in power.

What I love about this country in particular is that, despite the graveyard this country is built on, we still can harness these difficult conversations amongst us and appreciate and learn to value our differences, the differences that are equal in importance and equal in power.

KH: It’s difficult for any survivors to talk about their #MeToo stories, but I’d image that for you as a public figure, knowing that so many people will hear it, both in your op-eds and your talk about James Woods in the past, as well as your stories in the book, what does it feel like to come out with yours knowing that it’s so public?

AT: Sickening. It made me feel sort of sick. Just because it’s difficult subject matter for me and it’s things I’ve never really talked about. But it’s really interesting too, even when I was writing the book, Random House’s legal department had to vet those stories. They had to make sure that they were true, and even in that felt like, you can’t just take me at my word. And you realize that it’s not just about being taken at your word, it’s about protecting all of us because we live in a litigious society where if men get accused of sexual assault or sexual violence, a lot of the time the result is that they sue. There’s intimidation practices, I’ve learned so much through my work with Time’s Up from a legal and legislative policy standpoint, it’s crazy. And so I get it, I at least have a different experience and a different understanding of why those things need to happen. But it was tough. Tough to write about, tough to go back to.

About the Author

Amber Tamblyn is an author, actor, and director. She’s been nominated for an Emmy, Golden Globe, and Independent Spirit Award for her work in television and film, including House M.D. and Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants. Most recently, she wrote and directed the feature film Paint It Black. She is the author of three books of poetry, including the critically acclaimed bestseller Dark Sparkler, and a novel, Any Man, as well as a contributing writer for the New York Times. She lives in New York.

About the Interviewer

Katy Hershberger holds an MFA in Nonfiction Writing from The New School. Her work has appeared in Electric Literature, Catapult, TinHouse.com, The Rumpus, and elsewhere.

Amber Tamblyn on Owning the Worst Parts of Herself was originally published in Electric Literature on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.