CJ Hauser’s novel, Family of Origin, tells the story of two estranged half-siblings who journey to a Gulf Coast island inhabited by quack scientists—where their father, one of said quacks, has just drowned. Isolated on “Leaps Island,” these pseudo-scientists concoct theories about evolution moving backwards; they study a local species of curiously feathered ducks to “prove” it. They call themselves “Reversalists.”

The adult siblings, Elsa and Nolan Grey, approach the enclave, each other, and pretty much everything with skepticism. As they struggle to understand why their father, a once-respected scientist, spent his final years observing ducks in seclusion, a plethora of other discomforts bubble to the surface.

CJ Hauser is a veteran of the literary world: she’s worked at multiple literary agencies, taught writing from Florida State University to the Gotham Writers Workshop, and received awards including the McSweeney’s Amanda Davis Highwire Fiction Award, the Jaimy Gordon Prize in Fiction, and Narrative’s Fall 2014 Short Story Prize.

She currently teaches at Colgate University, where we met several years ago at the Colgate Writers’ Conference. I am obsessed with the Instagram account she shares with her dog, Dr. James Moriarty. Don’t worry—we talk more about him later.

Deirdre Coyle: When I started reading Family of Origin, I immediately looked up whether the Reversalists were a real collective (and found no evidence, of course). How did you come up with their theories?

CJ Hauser: I’d actually been working on a kind of post-apocalyptic novel before Family of Origin—but I was hating every minute of writing it so I took a step back to ask myself what was going wrong. And it turned out, I wasn’t interested in what the world looks like once the worst has already happened. I was interested in how the hell a person is supposed to go about their life when they feel like the apocalypse might be just around the bend, but they still have to live in a world full of parking meters and doodle scheduling polls and ketchup-flavored potato chips. What is a person supposed to do with that?

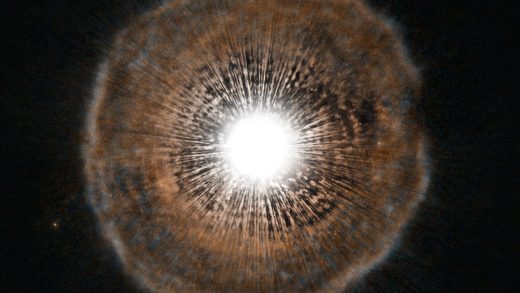

And that’s where The Reversalists came from. They’re a bunch of charmingly grumpy scientists who move to this remote island to do research, but really, to hide from a world they can’t bear. They believe evolution is running backward because of a seaduck they’re studying, but every one of them has a different reason the duck “proves” that the world is going backward ie getting worse. I was interested in the idea that a rational person could become so totally despairing that they would lose their ability to do good scientific work any more and would instead start bending their science to prove their sentiments correct.

DC: Are you particularly fond of any real-world pseudoscientific theories?

Under what circumstances is a person morally allowed to plug their ears and sing la-la-la while the world burns around them?

CJH: So, I fucking love lake monsters. I spent a summer on lake Champlain as a kid and desperately wanted to find Champie. I will someday visit Loch Ness. I have watched Lake Placid way too many times. I aspire to find Lauren Groff’s Glimmerglass lake monster when I swim in Lake Ostego. Quagmire is one of my favorite episodes of The X-Files (I would love to fight someone about that last one…)

I actually teach a class on science-writing and scientific literacy and we talk a lot about why people believe in pseudo-sciences. I think so much of it comes down to what people are missing from their real lives that pseudo-sciences are able to offer them. Sometimes that’s people needing a more tangible way to point fingers at the government (UFO cover-ups!) and other times it’s missing a sense of control over their lives (we spend a lot of time talking about crystals) and sometimes it’s just a desire for the world to feel a little more exciting and magical than it normally does.

I love lake monsters because I really need to believe in these creatures who are bigger and older and stronger than humans who have been swimming around before us, and will still be swimming after us. If I can believe in that, then I can feel slightly less worried about humans having irrevocably disrupted and destroyed the planet. If Nessie is out there, hey, maybe we’re not as big and destructive as I fear we are.

DC: In one of my favorite threads, Elsa wants to go to Mars, trying to escape the wretchedness in both her life and the world at large. Why did you hit on Mars for Elsa, instead of a more earthbound escape plan like Australia, or opioid addiction?

CJH: Okay so the Mars One program really did draft and interview colonists for Martian settlement. Real people applied! You can find profiles of the applicants and interviews with them online. Some of these people had lovers and kids and jobs and lives and I became obsessed: what would make a person give up on earth and take a one way ticket to Mars?

For Elsa, she’s incapable of just living her life because all the greater problems of the world immobilize her. She wants to feel like she’s doing something good in the world, but she can’t imagine any choice she could make that she would be sure was good. Or be sure wasn’t good at the expense of something else better. In her mind, Mars gives her a kind of moral certainty she doesn’t think it’s possible to have anymore in this age, on this planet. And, going to Mars is also a way of sheltering herself from the problems of Earth. In space, she won’t be on the hook for dealing with them. In a way, Elsa is doing the same thing the Reversalists are doing: placing herself in a position where she can pretend she doesn’t have any agency or responsibility for the world at large anymore. It’s like a DIY Island of the Lotus Eaters. In a lot of ways the book is asking: under what circumstances is a person morally allowed to plug their ears and sing la-la-la while the world burns around them. Spoilers: there are none. We are all of us on the hook.

DC: What’s great about terrible family dynamics is that most people can relate. The Grey children, of course, have unique circumstances. Did you have difficulty writing their particular dynamic?

What would make a person give up on earth and take a one way ticket to Mars?

CJH: Writing the Grey siblings was the struggle and the heart of the book. I think what made Elsa and Nolan interesting to me was the idea that they share their father, Ian (they have different mothers), but he was their father under very different circumstances and at very different times of their lives.

The collective Greys had, years ago, tried to create a kind of utopian blended family, but it backfired extraordinarily and split the family up—I wanted to explore how that history reverberated through Nolan and Elsa’s later lives. Because they are two people who know they are bonded together by something, but with their father dead and them having lived as strangers for years, they’re not exactly sure what that something is. Nolan sometimes refers to Elsa as his ex-sister.

This is one of my hobbyhorses: the conventional rules for how people interact depend on what their relationship is (mother/daughter, boss/employee) but how do you interact with someone when you don’t know what your relationship to them is supposed to be? Nolan and Elsa are supposed to act like brother and sister, but no part of their life has trained them to do that. And when you strip away the roles and labels and conventional rules from a relationship, suddenly the participants have to negotiate terms, and make mistakes, and make new rules. I never get sick of trying to get to the bottom of how two people might do that.

DC: If you were going to Leaps Island, what’s the #1 thing you’d want to escape?

CJH: What an excellent and troubling question. In the book’s opening there’s a list of things people are trying to escape, and the list ping pongs between huge important things like climate change to petty personal things like their inboxes.

I think there’s something about being a worrying human today that causes us to mentally leap from worrying over the email we haven’t answered to worrying about children separated from their parents at the border to worrying about whether our mother’s minor surgery will go okay to worrying about whether or not all the polar bears are dying and the world is coming to an end to worrying about whether the vegetables in the fridge have gone bad.

This kind of mental vacillation is strange and exhausting and narcissistic and an inescapable part of the way so many of us live our lives these days and this manner of worrying small/large/small/large is where this book came from for me. Because it’s paralyzing and how can you do anything, small or large, when this is what your brain is doing? If I ran away to Leap’s it would definitely be to escape these mental gymnastics. But I like to think I wouldn’t run. I like to think I’d stay.

DC: Let’s talk about your very good dog for a minute. How does he handle your writing life? Is he helpful?

CJH: Dr. James Moriarty, criminal mastermind, Mori for short, is an enormous and fluffy mountain dog. He is, in fact, a very good boy. He is not a fan of my writing habits. Ie: writing. Ie: sitting at a desk for long hours. He flops on the floor and grunts and sighs.

That said, I have rediscovered walks since he came into my life. I remember learning that Wordsworth composed while on long walks and thinking HA HA must have been nice simpler times. But now suddenly I’m this person who goes walking in the woods for hours and the way my sad-rabbit of a brain starts moving when I’m out there is definitely different and better for storytelling and story-problem-solving then sitting at a desk. I usually take Mori to a trail called The Darwin Thinking Path, and this felt spiritually correct as I was working on this book about a movement of people trying to corrupt Darwin’s thinking.

Dogs! Good for brains. Good for books.

The post Are Ducks Evolving Backwards? appeared first on Electric Literature.

Source : Are Ducks Evolving Backwards?