Time may not be linear, but that’s the way we puny mortals experience it. From our vantage point in an ever-fleeting present, we look back on the past with a variety of emotions, including regret. Would our lives be better if we had the chance to go back and call a do-over on what we consider to be our worst mistakes? Given the state of current technology, we won’t find out any time soon — and that’s probably a good thing. Just ask Anya Corazon and Miguel O’Hara.

|

|

In Alex Segura’s YA novel Araña and Spider-Man 2099: Dark Tomorrow, Anya/Araña is on the trail of a stolen artifact when said artifact unexpectedly blasts her into the early 22nd century. There, she meets Miguel, the former Spider-Man 2099, who is no stranger to time travel. But Miguel gave up being a hero after traumatic personal losses, and it will take the gravest crisis imaginable to convince him to put on his costume and be a hero one more time.

Since time travel is integral to the plot, reading this novel got me thinking about the different ways time travel has appeared in superhero stories — some good, some bad. Along the way, Segura was kind enough to answer my questions about Dark Tomorrow and time travel stories in general. If you care about spoilers, read freely: there are none here — at least, none for Dark Tomorrow.

Just a Jump to the Left…

Time travel stories predate comics by at least several decades. Encyclopedia Britannica cites books like H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine and even Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol as early classics in the genre. The Time Machine was adapted as a comic book in the Classics Illustrated series, which Segura cited to me as a story that resonated with him as a young reader.

“I love [time travel stories], honestly,” he said. “The idea of hopping around time has always been of interest”

It has also been a part of the superhero experience since the early days. In the 1940s, Batman traveled back in time to pal around with D’Artagnan and the Three Musketeers in Batman #32 and into the near future to show what the world might be like if the Nazis were to win World War II in Batman #15. (Granted, this last one was less a story and more an attempt to scare the audience into buying war bonds.)

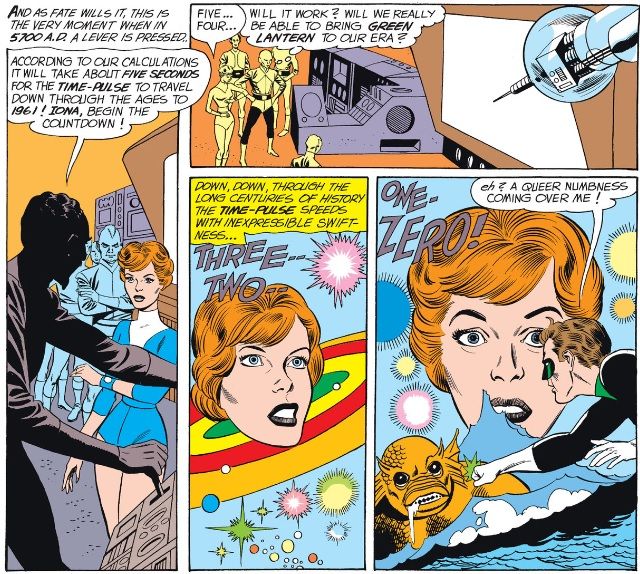

Time travel became a common plot device in the 1950s and ’60s, when stringent self-censorship precluded more violent kinds of stories. That’s how we got nonsense like Action Comics #148, in which Superman travels back in time to cheat Indigenous people out of the land Metropolis sits on, and Green Lantern #8, in which Hal Jordan is drafted into fighting villains in the 58th century because humans of the future are too pathetic to do it themselves (but not too pathetic to kidnap a 20th-century man and give him amnesia).

|

But there were more serious stories too. In the poignant yet retroactively hilarious Avengers #56, Captain America traveled back to the 1940s to convince himself that his sidekick Bucky was really dead. (Bucky was not, in fact, dead.)

This versatility is part of what draws Segura to time travel stories: they “can range from the funny to the painfully emotional,” he told me, “and I love the idea of affecting your own future or going back in time to see what things were like. The story possibilities are endless.”

As superheroes made their way into other genres, they took their tales of time travel with them. An episode of Freakazoid! has the titular hero prevent the Pearl Harbor attack, which somehow results in Rush Limbaugh becoming a decent person. In his 1978 film, Superman reverses the Earth’s rotation, which also reverses time and allows him another chance to save Lois Lane. (It goes without saying that that’s not how science works, but okay, fine.)

And then there’s the star of The CW’s The Flash, Barry Allen. Oh, Barry. Damn it, Barry.

With Great Power Comes Great Irresponsibility

The Flash may be more closely associated with time travel than any other hero (which I’m sure upsets Booster Gold, a 25th century ne’er-do-well who traveled to our time to become a heroic gloryhound). Early on, he learned he could travel through time by running on the Cosmic Treadmill. Some of his biggest foes — Reverse-Flash and Abra Kadabra — and his closest allies — his wife Iris West and their grandson Bart Allen — come from the future. Barry would later abuse his ability to time travel in both the comic Flashpoint and the TV show The Flash, when he rewrote all of reality to bring his murdered mom back to life.

This storyline is where I started to view time travel tales differently. Even more than Ray Bradbury’s A Sound of Thunder, this is the story that made me realize the ethical pitfalls of time travel.

Unlike Eckels, the hapless protagonist of Bradbury’s classic story — or even grief-stricken Superman impulsively reversing the Earth’s rotation by a couple of minutes — Barry Allen makes a conscious decision to change the past. As Reverse-Flash gleefully puts it, “You traded the life of your mother for the rest of the world!”

|

And Barry’s action is not without consequences. In both the comic and the TV show, the lives of Barry’s friends turn out vastly different — and sometimes worse — than how they were before.

As Segura points out, consequences are another reason that time travel makes for such a fascinating subject. In particular, he cited the “emotional stakes” — the inevitability of revisiting painful events or dead loved ones, or of seeing future events you may not like — as being especially high and therefore especially interesting. I can certainly agree, but personally, I have trouble sympathizing with a supposedly heroic character who willingly (and, in the TV show, more than once) messes with something as dangerous as time because he can’t handle being sad or accept his mistakes.

Obviously, Barry has the right to be upset over his mother’s death, even years after the fact. But you don’t get to ruin countless lives just because you can (it seems unlikely that Barry’s friends are the only ones who got screwed over, out of all the billions of people in the world). He allows his grief to make him selfish, even villainous. Who else but a villain tries to remake the world as they see fit? Go to therapy like the rest of us, bud.

Fortunately, Dark Tomorrow is more judicious in its use of time travel: Anya doesn’t do it on purpose, and Miguel only did so when the world was in danger. But Segura acknowledges that Miguel’s pain, much like Barry Allen’s, could have driven him down a darker path.

“[I]t’d be weird if he wasn’t” tempted to go back in time and prevent his personal tragedies from occurring, Segura says. “But I think one of the lessons Miguel learned early on was the fragility of time travel, and how the timeline tends to right itself or protect itself against major attempts to alter it….At his heart, Miguel is a scientist, and has probably grappled with these questions regularly when caught up in his time travel adventures!”

In other words, the heroes of Dark Tomorrow are not trying to remake the world in their image, so to speak. They’re just trying to save it, and in the process of doing so, they could end up changing a few things — probably for the better, but who knows what tomorrow will bring?

In the Not-Too-Distant Future…

So why do we still like all these time travel tales? Or, in my case, all of these tales except for those starring Barry Allen?

I think it’s a combination of everything I’ve covered: it’s high-stakes, it’s emotional, and it’s just plain fun. The appeals and temptations of time travel may be stronger for a superhero than for your average character, making for even richer storytelling. Righting wrongs is the superhero’s main reason for existing. If presented with the chance to use time travel to fix past mistakes, they’re sure to feel pressure to do so — and, in some cases, succumb to that pressure.

In Dark Tomorrow, the time travel is in part a simple necessity: Araña and Spider-Man 2099 exist a century apart, so the only way that they — Marvel’s two Latine Spider-people — could go adventuring together is through time travel shenanigans. But Segura believes it serves another purpose: to compare two very different worlds with surprisingly similar problems.

“Miguel’s Nueva York might seem shinier and more convenient than our New York, but as we dig deeper, we see some of the same problems crop up — and some of the same class issues and social situations,” Segura says. “It really helps hammer home the theme that you can be a hero whenever you are, and it takes the same kind of passion, dedication, and sacrifice.”

By opening a door to the past — or the future — time travel stories don’t just entertain us: they teach us the critical lesson that people are people, no matter where or when they were born.

For more time travelin’ superheroes, check out these lists about heroes wrecking the timestream and getting stuck in the past!

Source : Have Powers, Will (Time) Travel: Superheroes and the Urge to Change the Past