Walk into any Barnes & Noble, and you’re likely to find at least one table devoted to Greek mythology retellings. Mythology retellings, especially Greek mythology, are a hot commodity in publishing lately, you’ll see them showcased on TikTok and across Bookstagram. Google “Greek Mythology retellings” or a variation thereof, and you’ll see an abundance of “Must-Read” lists. Within publishing, literary agents and editors will list Greek mythology retellings on their wishlists, including it among the “vibes” they’re looking for when finding new projects. Think Madeline Miller’s Circe, Jennifer Saint’s Ariadne, Alexandria Bracken’s Lore, etc. All popular retellings based on Greek mythology, and all beloved by many readers. This in itself is okay, especially when retellings of any mythology are told through the lens of BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ voices. Yet among so many, or really most, of these lists, there seems to be a vital part missing, and people are starting to notice:

Where are the Greek writers?

They exist; diverse, talented, and a few of which are interviewed here. Yet we rarely seem them listed on “Must-Read” retellings, or included or invited to participate in Greek mythology retelling anthologies. This article does not seek to provide a single solution to the disconnect between Greek mythology retellings and Greek writers, particularly in publishing as of late. Rather, my hope is that this essay will do what we as readers so often want and ask for of stories: to give a perspective and a voice. To show a lens with which to view what we haven’t, or even knew to look for, before.

I recall an 2021 Esquire article, where the author wrote “mythology is back, baby.” To many, especially with whom any mythology is connected to as a culture, it’s not a trend; it never left.

Of a Particular People: What is Mythology?

To start, let’s keep in mind that Greek mythology, like any mythology — Norse, Aztec, Celtic, Egyptian — originated from a culture, compiled and passed down through millennia. That culture is made up of people who not only grew up with such stories but whose identity and heritage have been shaped around it inextricably. Merriam-Webster’s definition of mythology is: “the myths dealing with the gods, demigods, and legendary heroes of a particular people. The key phrase here: “of a particular people.”

In a time when so many mythology retellings show a wide diversity of voices, especially from people of whom the mythology originates from, Greek writers are curiously absent.

World Fantasy Award winner and Nebula and Rhysling finalist Natalia Theodoriou said this is what happens when you’ve been so thoroughly erased, people don’t even register the absence.

“As everyone feels they already know (or even own) Greek mythology, while modern Greek history and culture are deemed irrelevant/extraneous to it, Greek writers are considered unnecessary (if we are considered at all),” he said.

Greek Mythology vs. Western Mythology

When the exploration of identity and diaspora through fiction is so necessary for our society, there’s a fissure when it comes to Greek mythology. Perhaps it is because it’s considered a Western mythology. That is certainly true in that the United States and Western Europe has had (and continues to have) an obsession with Greek mythology.

Illustrator and designer Yorgos Cotronis said it’s obvious why there is a love for Greek mythology.

“It is to be expected that writers will be drawn to telling stories in this space

and remixing these myths,” he said. “I do think that Greek mythology has been placed near the top of what ‘ancient western culture’ is, although I would argue that Greece is not exclusively Western. It’s also pretty extensive, with a lot of little tidbits and side characters to play with, plus there’s something for everybody, from tragic tales of sacrifice to macho bloodied heroism.”

Eugenia Triantafyllou — a Nebula, Ignyte, and World Fantasy Award finalist — also talked about how Greek mythology has been layered into Western culture, and how the connection to Greek authors from Greek mythology has been lost.

“I think exactly because it has been assumed that Greek Mythology belongs to the Western canon that nobody thinks to connect it with modern Greece and modern Greek writers, which is in and of itself denying an important part of our cultural continuity,” Triantafyllou said. “Modern Greeks are not considered to have connection to their ancestors (although they very much do, especially in a deeply cultural way that cannot be easily understood by those on the outside). Modern Greek writers exist. Greek mythology also exists. It’s just that people didn’t think to draw a line from one to the other. It didn’t cross their minds.”

Rhysling and Elgin nominated poet and fiction writer Avra Margariti, adds:

“My theory is that U.S.-born writers seek Greek mythology as an open source that belongs to no one (therefore, it belongs to everyone),” they said. “So they claim this mythology as the shared creative world they crave.”

A Brief Summary of a Long History

The history of Greek mythology, its origins and complex machinations is, quite literally, thousands of years old. Let’s jump forward a bit to where we start to see some of the contemporary disconnect.

Neoclassicism: A Western Obsession

The Neoclassical movement — a style and art form inspired by Ancient Greece that began in around the 18th century after the rediscovery of Pompeii and Herculaneum — was essentially a Western cultural movement, hugely popular in Europe, and inspired by the writings of a white man, Johan Joachim Winkelmann. Europeans, particularly the English, thought Ancient Greek architecture and art were the pinnacle of sophistication, though they often misinterpreted it. And as colonizers are wont to do, they took it as their own. Now, as Theodoriou, Triantafyllou, and Margariti have touched on above, it’s become so ingrained in Western culture that many forget where it came from.

“Neoclassicism and Enlightenment were particularly obsessed with the ancients, and they were very influential in the young U.S. seeking its identity,” writer and performance storyteller Eleanna Castroianni said.

To go into the layered lengths, retellings, and (mis)interpretations that Greek mythology has been through, since before Nazi-occupied Greece, Greek Independence, before the Crusades, and before that, would be to peel a very large and very complicated onion. NC Kousis, historical fiction and fantasy writer, wrote an extremely informative overview of this history in “Greek Myth and Western Hegemony.” In it, Kousis writes, “To many, we don’t need stories from actual Greek people; Greek myth is part of the fabric of the Western world, in their opinion.”

Contemporary Hype

To continue on to today’s hype of Greek mythology retellings, Castroianni said the exploding trend is concerning, and points to the blockbuster series with Greek mythology at its core, like Percy Jackson, as a variable to why many believe Greek mythology can be constantly mined.

“The readership and the gatekeepers are from the U.S., and the U.S. has not really made the connection that Greek mythology is someone else’s mythology,” Castroianni said. “Maybe because of the connection the West feels with the ancients, it’s like Greek mythology is open source, free from copyright; go ahead, no one will sue you.”

Diversity and Community in Mythology Retellings

While most Greek mythology retellings in today’s popular trend, and past trends, have been told primarily by white U.S. and UK authors, we do see diverse voices, especially recently. This is excellent. Every Greek writer interviewed for this article agrees that the inclusion of BIPOC and LGBTQ+ voices is necessary. It’s also extremely important to note that, as in Ancient Greece as well as now, people of color existed in Ancient Greece and exist in modern Greece.

“I do think we need more work (and not just Greek myth retellings) by BIPOC authors, LGBTQ+ authors, disabled authors, non-Anglophone authors,” Theodoridou said. “I just wish people wouldn’t forget that Greek myth retellings that foreground diversity don’t need to exclude Greek writers. We are a pretty diverse bunch, after all, and many of us are marginalized along multiple axes.”

“I personally enjoy the ones that offer a unique perspective based on experiences usually under-represented by publishing, or a combination of cultures — these are the stories written by marginalized authors, who I believe have something new to offer to a genre of mythological retellings full of white, cishet, anglophone writers,” Margariti said.

The Science Fiction and Fantasy Community

Marginalized authors, especially in the science fiction and fantasy community, have noticed the disconnect between Greek mythology retellings and Greek writers recently, discussed in forums and across social media. Some have taken to Twitter to voice their concern. Nebula and Hugo award finalist Shiv Ramdas posted the following:

The conversation within the SFF community reflects a larger concern across publishing, and not just with Greek mythology retellings, but all mythology retellings across cultures. Discussion around this topic is about education and consideration.

“Personally, all I really need is for people to keep writing retellings but think very carefully about how they approach them (do you really need this myth to tell this story? whose story are you telling?), and for Greek writers to not be excluded but invited in those spaces (which should be obvious, to be honest),” Castroianni said. “If SFF writers and editors keep these in mind and make an honest effort, it is a start.”

Theodoridou also hopes that discussions within the SFF community and across publishing will not only invite Greek writers to the table of Greek mythology retellings, but to also allow Greek writers to write mythology retellings that don’t always follow what many consider mainstream or popular.

“Some of us have been told that the mythological figures we’re interested in retelling are too obscure for American audiences,” they said. “I hope publishers are brave enough to be willing to venture beyond the well-trodden occasionally. Perhaps we just need to have more faith in readers’ ability to cope with the unfamiliar.”

Greek Creators: Where to Start

One of the most important points of this essay is to spotlight Greek writers who are publishing great Greek mythology retellings. Below is a list of works across mediums, including work by those interviewed here and those they have recommended. All are great work to explore and uplift.

Greek Mythology Retellings: Novels by Greek Authors

Threads that Bind by Kika HatzopoulouThis Greek mythology-inspired mystery takes place in a world where descendants of the gods inherit their powers. Io, a descendant of one of the Fates, uses her powers to as a private investigator. In the city of Alante, someone is abducting women and mutilating their life threads to create dangerous wraiths that are let loose upon the city. Io must use her powers and investigative skills to find the culprit while also navigating emotions around a boy who shares a thread with her, linking them as soulmates. |

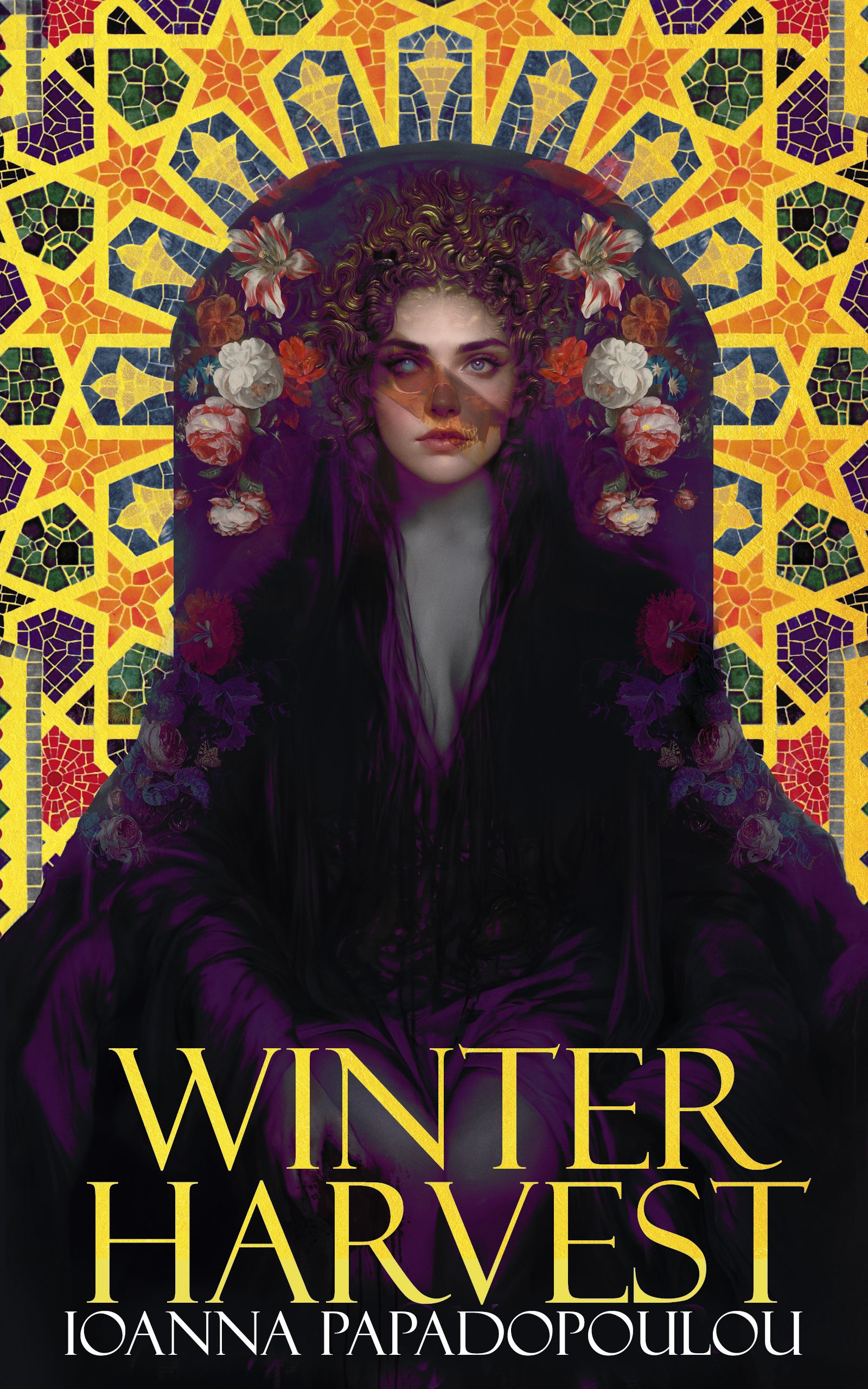

Winter Harvest by Ioanna Papadopoulou (November 2023Forthcoming from Ghost Orchid Press, this tale focuses on the goddess Demeter, daughter of Kronos and Rhea. A feminist exploration of a goddess’s role in a patriarchal hierarchy of gods, this is a book that takes what we know of Demeter and dissects its layers, the rage and emotion of being the mother of a missing child, and finding our place in the wide world. |

An Odyssey: Echoes of War by Natalia TheodoridouThis is a unique longer work, as it is a novel that is also an interactive game. Readers embark on a retelling of Homer’s The Odyssey: Troy has fallen, and you, the reader, are the crowned sovereign of Ithaca. You must make your way home, but Poseidon has cursed your journey. This is an action-packed and poignant retelling of The Odyssey, a story told within a story, with the reader at the helm. This is not Theodoridou’s first run at interactive gaming, either, having also been nominated for a Nebula award for his Choice of Games’ title Rent-a-Vice. |

Greek Mythology Retellings: Short Stories by Greek Authors

- “Notes from the Laocoön Program” by Phoenix Alexander in Metaphorosis, a retelling of the myth of Laocoön

- “Darkness, Our Mother” by Eleanna Castroianni in Clarkesworld, a retelling of the myth of Ariadne and the Minotaur

- “Bride of the Gulf” by Danai Christopoulou in khōréō magazine, a retelling of the myth of Thessalonike

- “Kairo’s Flock” by Avra Margariti in Lackington’s, a retelling of the myth of Icarus

- “The Names of Women” by Natalia Theodoridou in Strange Horizons, a retelling of the myth of Philomena

Greek Artists and Filmmakers

Greek artists and filmmakers are also doing important work expanding the definition and style of Greek art. It’s not always what we think, though cliches are often leaned on.

“As an artist, the cover art I see for most of [Greek mythology retellings] (with some bright exceptions) usually follow the publishing rule of being ‘to market,’ “Cotronis said. “Some ancient Greek patterns, Greek pottery style paintings, orange and black hues, one of those awful “Greek” fonts that are unreadable to any Greek and turn “Cleopatra” to “KLSOPDTRD.”

You can find Cotronis’s artwork on magazine covers like The Dark, and book covers, such as Scott J. Moses’ Our Own Unique Affliction and the forthcoming Greek mythology retelling from Ghost Orchid Press, Winter Harvest by Ioanna Papadopoulou.

And as mentioned earlier in this article, there are people of color throughout Ancient Greece as well as in Modern Greece. Filmmaker Adéọlá Naomi Adérèmí created I am Afro Greek, a film about the lived experiences of Black people in Greece. In an interview with Contemporary And, a visual arts platform, Adérèmí describes the structural racism we see around the world present in Greece as well.

“Invisibility is a very double-edged sword, when you come from an allegedly homogenous white country, that is Greece,” Adérèmí said in the article. “I say allegedly because it’s not true. Greece has always been a migration country. But when it comes to internalized structural white superiority, through media, through art, we as Black people have never been represented.”

Continuing the Conversation

To continue to show new perspectives in the creation of stories, whatever medium they’re in, is so important in today’s world of rising hatred for marginalized people. This overview might not provide a clear solution, but giving voice to it is a start. It’s about the discussion, about asking questions. And it’s important to keep constant vigilance in whose stories we’re telling or retelling, whose cultures we’re presenting, and why.

Triantafyllou notes that Greek populations and Hellenistic influences are seen in southern Italy, Cyprus, and Egypt. It would be great to see interpretations of Greek mythology from writers connected to those cultures as well.

“I think what is happening here is a good start,” Triantafyllou said. “People don’t know the whole about how Greek mythology came to be so popular in the West. Just this article reaching and educating some people in some ways is a good thing.”

Part of my past work for Book Riot includes spotlighting literary magazines and presses that, in turn, spotlight work from marginalized groups, such as queer writers, Black speculative fiction writers, and immigrant and diaspora writers. As a privileged person given an opportunity to write, this work is so important, and will continue.

Source : In a Wave of Greek Mythology Retellings, Where Are the Greek Writers?