Brandon Hobson discusses indigenous identity and the foster care system

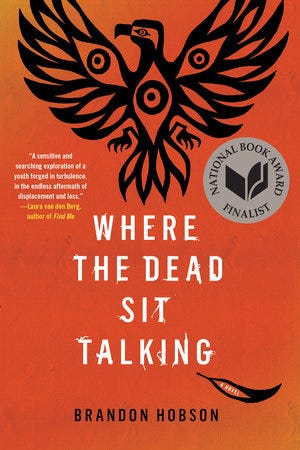

Where the Dead Sit Talking is a dark, twisting, emotional novel about a teenage Cherokee boy dislocated in the foster care system. Sequoyah has moved around to many homes, sometimes living in shelters while waiting in the in-between, not ever fitting in where he is placed. And then he is placed with the Troutts who have two other foster children, Rosemary and George. Like him, Rosemary is yet another American Indian child in the foster care system, trying to connect to a home.

The novel holds a difficult dialogue on intergenerational trauma, the effects of separating children from their Nations, and the perilous outcomes if we do not make urgent changes to the systems forcing American Indians to assimilate and disconnect. This may be set in the past, however, the same cycles exist today, showing that we have not yet learned the necessary lessons to interrupt the trauma.

Melissa Michal: What was the origin of the novel?

Brandon Hobson: It started with thinking about my previous work experience in social work. I worked for about seven years with delinquent and deprived kids and saw a common theme of a struggle with identity and a tendency toward obsession that I found really fascinating. At the same time, I also knew I wanted to write something from my Native culture. So I knew that having worked with Native kids in both delinquent and deprived environments that that was an avenue that I wanted to explore, specifically with my tribe which is the Cherokee nation. So I wanted to focus thinking about Indigenous youth in the foster care system. So that’s kind of where it all started. And the idea of “What is home?” is the important question I wanted to begin with.

So many of these kids struggle with that question of not knowing where their home is, right, because so many of these kids are shuffled around from shelter to shelter from foster placement to foster placement. So they don’t know where they’re going to be that next night and so forth. So that question also goes back to the historical significance of the Trail of Tears which is one of the worst events in US history which when people were removed from Georgia and North Carolina, people were faced with that very question, “What is home?”

I worked for about seven years with delinquent and deprived kids and saw a common theme of a struggle with identity and a tendency toward obsession.

MM: Describe for me your writing process getting into that kind of mindset, going to the places that those foster children have gone mentally. Sequoyah is very disconnected in this way.

BH: I heard his voice. Sequoyah’s voice is really strong in my head. It may have been a culmination of a lot of the youth that I have worked with, I think. Which at times it can sound very dangerous. It can also sound, I hope, very wounded. There may be a fine line between what sounds dangerous and what sounds wounded.

MM: Was Sequoyah always the main character? Did Rosemary change over the course of writing the novel?

BH: I knew early on that I wanted to have him look back at this short time that he was with the foster family and talk about her influence on him. And that’s where I think the novel gets a little bit obsessive or where the novel talks about his obsessive behavior and why is Sequoyah telling this story. A large part of that has to do with Rosemary dying in front of him. I’m not so much interested in the idea of writing about her death as much as I was interested in his fascination with her. Because of them being the only Indigenous foster kids in that home.

He’s also exploring identity issues with his gender and with his overall appearance. In 1989 not many boys wear eyeliner to school. I certainly think it’s way more accepted now then in 1989. Sequoyah is a little more androgynous which I wanted him to be. So I think early on I didn’t want to focus so much on her death as her impact on him. Both internally and externally. Not only the way she looked but the way she dressed and the way she talked. He felt very much, as did she, that they were connected on some other level that he could communicate with her on some other level, through the mind. There was some higher level of connection between them.

MM: Sequoyah’s focus on death becomes an obsession after meeting Rosemary. Where do you think this comes from for him?

BH: I don’t know if it’s just death. I think it just some other worldliness is what it feels like to me. Not so much death as other consciousness. I feel like he can communicate with her. Maybe not so much just what we think about death, but the idea of some other worlds some other consciousness that exists out there that maybe works in terms of communication. He felt very strongly. And she does too when she first meets him. She says “I knew you were supposed to come here.” In a way I think she was expecting him. And all of that exists on some other alternate universe. Or at least that’s how they both feel. I’m more interested in the emotional than the logical.

MM: Why set the novel in a past time period versus a more contemporary time period?

BH: A lot of that was just because it was my memories of being young and being a teenager in the ’80s. I wanted it to be pre-cell phone. For example, Rosemary she goes missing for a while. Before cell phones a lot of times people would just be, “Where are they?” I remember a couple of times my mom would just get out and drive and look for me before the cellphone when I was a teenager. That’s when the missing becomes harder to find. With iPhones now you can find pretty much find anyone quickly.

A lot of the music and pop culture that are mentioned in the book are the ’80s like the movie Rain Man is about an autistic man and George is autistic. That was out at that same time and part of that was filmed in Oklahoma. I remember when that was filmed here. And so there was a connection between that in the movie, the brotherly relationship, you know, George and Sequoyah struggling through that. So there were a lot of things that mirrored what was happening in terms of the ’80s. And band names as well. George memorizes lyrics and band names at a time when maybe people paid more attention to liner notes, the idea of the mixed tape and writing down lyrics. So it’s a pre-cell phone, pre-internet time. George is writing his novel, but he’s writing it on a main hard drive.

MM: What other writers/artists influenced your techniques in this novel?

BH: James Welch was a big influence. Diane Glancy. Those are two Native influences on me. Don DeLillo stylistically has always been an influence on me. More currently Ottessa Moshfegh and Laura van den Berg. Those are two young women writing right now who are amazing and two of my favorite writers that are currently writing. N. Scott Momaday has always been a huge influence as well.

MM: Is there any question or something about the novel that you have wanted to talk about, but no one has asked you?

BH: Ultimately it’s a story of home. A lot of people don’t ask about the identity issues. A lot of people aren’t asking enough about Sequoyah’s identity, exploring his gender issues and trying to decide you know I think that’s a big question that teenagers ask, “Who am I? What is my identity?” So while he’s exploring his Native identity he’s also a little bit androgynous. I just don’t know if that’s being written about very much, the question of androgyny especially in Native youth. We want to break through the stereotypes of how non-Indigenous people see Indigenous boys or girls as well. I basically didn’t want it to be just a stock Native character that falls into stereotype.

We want to break through the stereotypes of how non-Indigenous people see Indigenous boys or girls as well. I didn’t want it to be just a stock Native character that falls into stereotype.

MM: I wonder if that’s why people aren’t asking you, though. You do avoid those pitfalls. And so those kinds of stereotypes and pitfalls can then lead themselves to those questions of identity more so.

BH: There’s been a lot of talk about identity. But most people just ask how disturbed he is and how dangerous. They tend to think he’s a bad bad person and that’s he’s a super psycho path and that sort of confuses me as to why people would just automatically assume that.

MM: I think I got where the book was coming from. I also understand it at a different place because I have felt it as a Native woman. There’s a certain amount of rage and grief that you go through as a Native person that they haven’t gone through.

BH: It makes him a cross of all of that teenage rage and angst that may come across as more than I intended. Maybe I could have made him more empathetic. I don’t know. I mean again, it comes out of a place of a lot of my experience dealing with delinquent and deprived youth.

MM: I wonder if that gets stereotyped a lot, too. And this is a rounded character that has emotions and feelings and experiences that arise out of being in the foster care system, being Cherokee, being androgynous, and kind of exploring his identity in those kinds of ways. That’s a lot of intersections in the ’80s to manage.

BH: I hope that I pulled it off. It is a lot.

MM: I think that this last part of our interview is important to include. To be honest, I didn’t assume him dangerous. I saw him as broken and traumatized.

BH: Yes.

MM: And there were energies that were interacting with him and he was picking up on negative energies that just were keeping him from a positive place.

BH: Yeah. That’s how I want him to be taken.

About the Author

Brandon Hobson is the author of the novel Where the Dead Sit Talking, a finalist for the 2018 National Book Award for Fiction, and other books. He has won a Pushcart Prize, and his work has appeared in magazines such as The Believer, The Paris Review Daily, Conjunctions, NOON, Post Road, and in many other places. He is an enrolled citizen of the Cherokee Nation Tribe of Oklahoma.

About the Interviewer

Melissa Michal is of Seneca decent. Her creative work explores historical trauma and resilience within her own community. Her criticism focuses on trauma and representation of Indigenous histories and literatures in educational curricula. She is a fiction writer, essayist, scholar, and a professor. Her short story collection, Living On the Borderlines, is out with the Feminist Press in February 2019 and was a finalist for the Louise Meriwether first book prize. Melissa has work appearing in The Florida Review, Yellow Medicine Review, and other places. She has finished her novel, Along the Hills, and non-fiction collection, Broken Blood, and is now working on her critical monograph and second novel.

In “Where the Dead Sit Talking,” a Native American Teen Searches for Home was originally published in Electric Literature on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Source : In “Where the Dead Sit Talking,” a Native American Teen Searches for Home