Poet Maggie Smith’s debut memoir, You Could Make This Place Beautiful, is about the end of her marriage, grief, motherhood, the pain that comes with change, and where she found herself in these moments. Her prose, like her poetry, is gorgeous and moving. The feelings conjured are flipped and turned and examined from underneath.

Divorce, although common, still feels racy, somehow. A little ominous, and taboo to write about. I’ve been divorced for a couple years, and people still don’t know how to talk to me about it. They jumble words. They awkwardly pause. They ask questions they don’t want truthful answers to. You just want to scream, “I’m the same person!” But this instinct is wrong. Because you’re not the same person. Like Smith says, you’re a nesting doll of yourself. The married person you were, inside the person you are now. Still, you want to be treated the same. You want to feel like you are the same. But you, and that usually well-intended person standing in front of you, know you will never be the same. And that is absolutely okay.

The truth of it is, it’s all just a mess. A beautiful, beautiful mess.

You probably know Maggie Smith from her viral 2016 poem, Good Bones, or her collection, Keep Moving: Notes on Loss, Creativity, and Change, or any of the six other collections she’s written. But you will definitely know her now from this powerful and tangibly raw memoir:

“I’ve wondered if I can even call this book a memoir. It’s not something that happened in the past that I’m recalling for you. It’s not a recollection, a retrospective, a reminiscence. I’m still living through this story as I write it I’m finding mine, and telling it, but all the while, the mine is changing.”

Hoda Mallone: You call yourself a “half-double—half a couple, half a whole,” when you begin the book, then get to a place where you feel “whole.” Do you feel like the process of writing this, helped you find that wholeness?

Maggie Smith: One of the narratives around marriage, it seems to me, is the story of finding someone who “completes you”—your missing half. According to that story, divorce is a halving, a split of a whole into two (diminished, lesser) halves. Certainly in the initial shock and grief of my marriage ending, I felt diminished. But of course that whole story—no pun intended—is a lie. We’re whole on our own. The process of writing the book helped clarify this for me, sure, but it was the process of living post-divorce that helped me see it most of all: I’d been there, whole, all along.

HM: Recently, I had an interesting conversation with authors about the “female protagonist.” Would you consider your character (you) a protagonist? Did you consider how she would be viewed by readers in this light?

MS: If I’m not the protagonist in my own life story, then who is? Or, maybe more to the point: If I’m not the protagonist in my own life story, then where could I ever have that agency? I mean, I’m certainly not the main character in anyone else’s life, even if I am a main character. But I also don’t see myself as a character in this book, I just see… me. I break the fourth wall in this book by speaking directly to the reader, as myself (the writer, the woman, the mother, the daughter, the friend). Maybe my consciousness is the protagonist.

HM: In the chapter, “An Offering,” you describe the idea of “possession.” You say, “The anger possesses you—owns—you.” How do you believe women being angry or expressing anger is regarded in our culture, in your experience?

MS: I don’t think there’s any acceptable way to feel or behave if you’re a woman, to put it plainly. If you’re angry, you’re cast as shrill, vindictive, out of control, even “hysterical.” If you’re calm, accepting, and forgiving, you’re cast as a doormat; you should be angrier! If you cry too much, you’re weak and overly sensitive. If you don’t cry enough, you’re cold and not “feminine” enough. If you’re unhappy, you’re a downer and lacking proper gratitude. If you’re happy, you must be dim or at least in denial about the world. There is no acceptable feeling if you’re a woman, so I say we give ourselves permission to feel our feelings, all of them. Can I say “fuck it” here, because that’s what I want to say: Fuck it.

HM: “Betrayal is neat.” Indeed, I agree. It gives an out to the other side, the victim, the betrayed. You could have taken that route in assessing your marriage. Why did you decide to do the opposite? To become more self-aware and exploratory with your introspection?

MS: Because I wanted to tell the truth, and the truth is never that uncomplicated. I wasn’t interested in writing a book in which I was the “good guy”—a victim, a martyr—and someone else was the villain. I knew in my heart that there were many, many hairline cracks in my marriage, not just one or two big fissures, and that I created, or at least co-created, some of them. Gina Frangello says that memoir has two essential ingredients: self-assessment and societal interrogation. I didn’t hear her say that until after I’d published my book, but I think You Could Make This Place Beautiful has them both. The self-assessment piece is critical.

HM: You talk a lot about the spaces between. The empty places. The quiet parts. What did you find when you looked into those?

There is no acceptable feeling if you’re a woman, so I say we give ourselves permission to feel our feelings, all of them. Fuck it.

MS: White space for me, as a poet, is incredibly important. The white space in a poem is literal breathing room—space for the reader to pause, breathe, sit with what you’ve just handed them, make connections within the book, and reflect on their own lives. A lot is possible inside that “empty” space, which isn’t empty at all, if you think about it—the reader fills it. I built a lot of white space into this book for that reason, to invite the reader to participate more. The “spaces between” in my life are places, too, where I was able to linger, listen, pay attention, reflect, and see things a little more clearly.

HM: After my divorce, I found that people in my life used it as an opportunity to examine their own marriages. Some were not so happy about this opportunity and often projected their fears or judgement onto me and my choices. It seemed like they were upset with me for making them think about the unthinkable. Did you find that to be your experience?

MS: I think divorce is still a taboo subject for this very reason. Divorced people are triggered, dragged back into the pain of their own experience. Happily married people don’t want to think that this dark shadow could fall on their house, too. I don’t think any of this is “unthinkable,” though, not really. Few things are truly unthinkable. What scares us most are the very painful “thinkable” things that happen all too often. Divorce is one of them.

HM: When you discuss making yourself small, declining work and income, withholding good news, it made me irrationally angry. Especially because all your sacrifice did not have the intended result: saving your marriage. Did you, at any point, find yourself angry?

The white space in a poem is literal breathing room—space for the reader to pause, sit with what you’ve just handed them, and reflect on their own lives.

MS: I was definitely angry at times, but I think beneath that anger was hurt and disappointment. Because if the person who should be your biggest cheerleader isn’t—well, you think, why not? I take a lot of comfort in the relationships that some of my friends have—people supporting one another, wanting the best for the person. As I see it now, I think we should want for our partners what we want for our children: the best lives possible. If we don’t want that, then what are we doing?

HM: What do you believe it means to be “good at being a wife?” In “Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing,” you question if you were. Do you still question that?

MS: No, I don’t. Relationships are challenging, but I don’t think they’re harder for me than for anyone else.

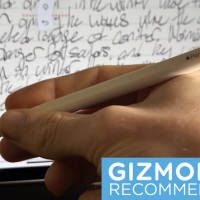

HM: I’d love to know more about the moment, after signing your divorce papers, when you looked down and saw your pen in your hand. Even though you weren’t married anymore, you always had writing. What did you feel in that moment of realization?

MS: It’s funny—I couldn’t have written that moment into a novel. It was too on the nose! But that’s exactly what happened, and so there you have it. I remember looking down, seeing the pen, and thinking yes. I still had—have—myself. I still have the writer I am. Joy Harjo has written about writing as sovereignty, and I love that. In that moment, it hit me that while a big part of my life was gone—not just my husband but my family unit, my sense of security, my sense of my own future—I was still there. The me of me.

HM: “The Intangibles” really hit hard for me. When a long relationship is over, so are all the small things (inside jokes, notes, made-up songs, knowing glances). Where does all the shared history go? Where have you managed to put it all?

I wasn’t interested in writing a book in which I was the ‘good guy’—a victim, a martyr—and someone else was the villain.

MS: There’s no place to “put” it. It lives inside me, and pieces bob to the surface now and then, and sometimes I’m able to smile and remember, but sometimes it just wallops me. And the walloping isn’t me missing my husband or wishing we were still together—it’s not that at all. The walloping is the cognitive dissonance of realizing all of that was real, and all of this is real, and it’d hard to square the past with the present. I can’t “put” that anywhere. I just feel my way through it, talk to my therapist about it, breathe, and write.

HM: You end the book talking about acceptance in lieu of forgiveness. I love this. But I still think forgiveness feels more healing than acceptance. Do you feel like you’ve come around to forgiveness as more time has passed? Or does acceptance suffice?

MS: Acceptance will have to suffice. Like, “We are humans, and humans sometimes hurt one another.” Like, “In a life many things happen, and these things happened.” I’ve come to terms with what happened, and I’ve even accepted the outcome, the divorce, as unavoidable. But I don’t think it’s my responsibility to forgive. I can let go without doing that.

HM: Your book is going to deeply touch many, many people, I suspect. Your story is relatable and honest and you. What advice can you leave for those who come to your work for clarity, or at the very least, to feel less alone in their situation?

MS: My hope for the book was a seemingly small one: that someone might read it and feel seen. That someone might read it and feel less alone. Some people may read the book as part cautionary tale, I suppose, and in that regard, I hope women in particular reflect on the space they feel permitted to take up, and the attitudes of their partners toward their work. I want us all to dream bigger and be supported doing just that.

The post Maggie Smith Finds Beauty in the Disillusionment of Her Marriage appeared first on Electric Literature.

Source : Maggie Smith Finds Beauty in the Disillusionment of Her Marriage