The scene takes place in a disco. Girls are wearing miniskirts, bikini tops, and layers of glitter. 20-somethings are dancing to psychedelic music and guzzling liquor straight from the bottle. A few couples are kissing, ensconced in corners of the club. It could have been a scene from , has been translated into English, published for Anglophone readers just last year. In his foreword, the book’s translator, Jonathan Smolin, declares, “It is shocking that Ihsan Abdel Kouddous is still largely unknown outside the Arab world.”

When I began to research Egyptian feminist literature for my MFA thesis, I too was shocked that I couldn’t find any of Ihsan’s work translated into English. Before I had ever thought of studying him, I had been introduced to him by my family who lived in Egypt during the peak of Ihsan’s fame. He was a familiar song that played in the background of their lives and, as I’ve come to learn, the lives of so many Egyptians during that time. He used to frequent the same Nile-front supper club at the Semiramis Hotel where my parents spent many a date night in the ’70s.

As teenagers, my aunt and her friends would sneak the latest issue of Rose El Youssef into their French class to surreptitiously read the next installment of Ihsan’s serialized novels, passing the magazine from one lap to the next. My aunt explained that Ihsan’s work was too risqué for a Catholic school run by nuns, but that it was too irresistible for avant-garde girls coming of age. “It was considered scandalous,” she recounted as she sipped her tea in my family room. “He was called ‘the bedroom writer.’” She smiled mischievously. “And we read him voraciously. Of course, everyone denied having read him. You have to remember how taboo sexual freedom was at the time. We loved Ihsan. We loved everything about him.”

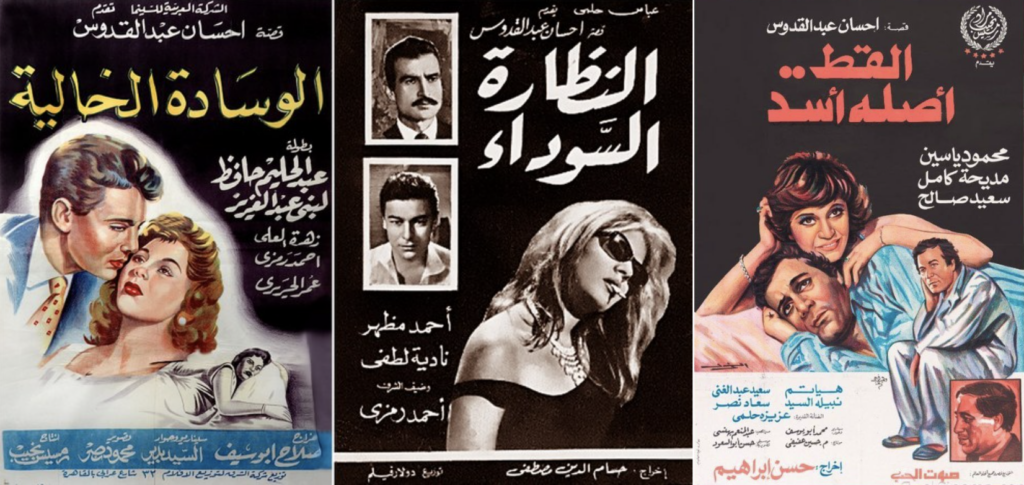

I had to know more about Ihsan. I can read some Arabic, but I’m not proficient enough to get through an entire novel, so with the help of my family and YouTube, I embarked on an Ihsan movie marathon and watched 12 of his film adaptations. While the endings had been changed by Egyptian censors, it was enough to get a taste of Ihsan’s flavor of fiction.

What I saw onscreen was the Egypt of my parents’ youth. In Anna Hurra (I Am Free), college girls defy entrenched patriarchal authority. In La Anam (I Do Not Sleep), a young woman sneaks out to spend the night in her boyfriend’s bachelor pad. And in Abi Fouq Al Shagara (My Father Is Up a Tree), a group of undergrads spend a summer on the beaches of Alexandria in spring-break-esque exuberance, girls in tiny bikinis running into the crashing waves, lovers kissing under the setting sun. I have photographs of my own mother in her yellow bikini posing on the same seashore. It was the side of Egyptian society I’d always heard about from my family who had lived in Cairo at the time but rarely read about in translated Egyptian literature. There was no permanent record. Why was there a vacuum where Ihsan’s work should have been?

I talked with Smolin, the translator of I Do Not Sleep and professor of modern Arabic language and literature at Dartmouth College, to figure out the answer. What I learned from Smolin is that my life and Ihsan’s life were set on their trajectories by the same dictator, Gamal Abdel Nasser, and that Ihsan’s work was much more than just an exposé of the liberated Egyptian middle class of the latter twentieth century. It was a cathartic admission of guilt, a veiled criticism of the military regime he’d unwittingly helped create. Like my father and many other Egyptians of the time, Ihsan had dreamed of ridding Egypt of the British-influenced monarchy that had reigned for 148 years and replacing it with a democracy. According to Smolin, Ihsan was friends with Nasser, then a member of a group of revolutionaries called Free Officers, and used his platform at Rose Al Youssef to call for a coup. King Farouk put him in jail for his treason in 1948. When Ihsan was released just under a year later, he forged on.

His writing eventually helped turn the tide of popular opinion. By 1952, he’d helped prime the nation for a revolution. But Ihsan was not ready for what was to come: a military dictatorship led by Nasser, who would rule with an iron fist. When he dared to disagree with Nasser’s violent, suppressive, and autocratic regime, Nasser, too, put him in jail, wielding the very power that Ihsan had helped him attain to imprison his former friend. When Ihsan was released, he resumed his writing. He never again explicitly criticized Nasser—rather, his new fiction became richly symbolic.

With the 1952 revolution came socialism, and over time there was catastrophic economic collapse. Dark clouds loomed over the futures of college graduates, among them my father, then a young doctor. With few professional prospects under Nasser’s regime, he sought to emigrate to the United States. But the same hand that had imprisoned Ihsan also forbade any doctors, lawyers, or scientists from leaving the country, an attempt at curtailing an already massive brain drain that turned Egypt into a quasi-prison for a large swath of its citizens. In a stroke of luck, my father convinced a government official to give him a visa to Lebanon and was allowed to leave the country. He went to Lebanon, and then to Detroit. My mother soon joined him there, and few years later, I was born. My father still shudders at the thought of what might have been, had he been forced to remain in Egypt under Nasser. “Just one small mishap, and we wouldn’t be here,” he often says.

Ihsan, on the other hand, was “haunted by Nasser.” According to Smolin, nearly every one of Ihsan’s novels symbolically exorcises his guilt for having brought a traitor into his country, his “home.” I Do Not Sleep is about a young girl who makes up a story of her stepmother’s infidelity to get rid of her; later, when she sets her father up with her friend, she learns that the friend is only after her father’s money and already has a lover. The theme repeats over and over again in novels like Al Tareeq Al Masdood (The Blocked Road) and Abi Fouq Al Shagara (My Father Is Up a Tree). Yet none of these works is available in English. I asked Smolin why that was.

“It wasn’t just the sexual taboos,” he said. “Ihsan wasn’t trying to appeal to the literati. He used simplified Arabic to expand his audience for the purpose of participation and debate in the press.” Because of this, Ihsan was seen as lowbrow, and nobody in the literary community suggested his work as a candidate for translation. In fact, Smolin said, up until 1988 almost all translated works were published by the American University in Cairo Press.

But without access to Ihsan’s work, we lose a vital link to life among educated middle-class Egyptians during the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s—what they thought about, the records they listened to, the movies they watched, the sex they had and the way they had it. Most of Ihsan’s stories are narrated by female characters and set against the backdrop of a cosmopolitan Cairo—a perspective largely absent from translated literature from the Middle East, and especially Egypt. As long as the vast majority of Ihsan’s writing goes untranslated, Egypt remains distorted and obscured in the imaginations of Anglophone readers. Smolin’s efforts give us just a glimpse into a body of work that could transform the way we think and talk about Egyptian life and literature—the rest of Ihsan’s oeuvre is an invaluable treasure just waiting to be unearthed.

The post The Forgotten Novelist Who Remade Egyptian Cinema appeared first on The Millions.